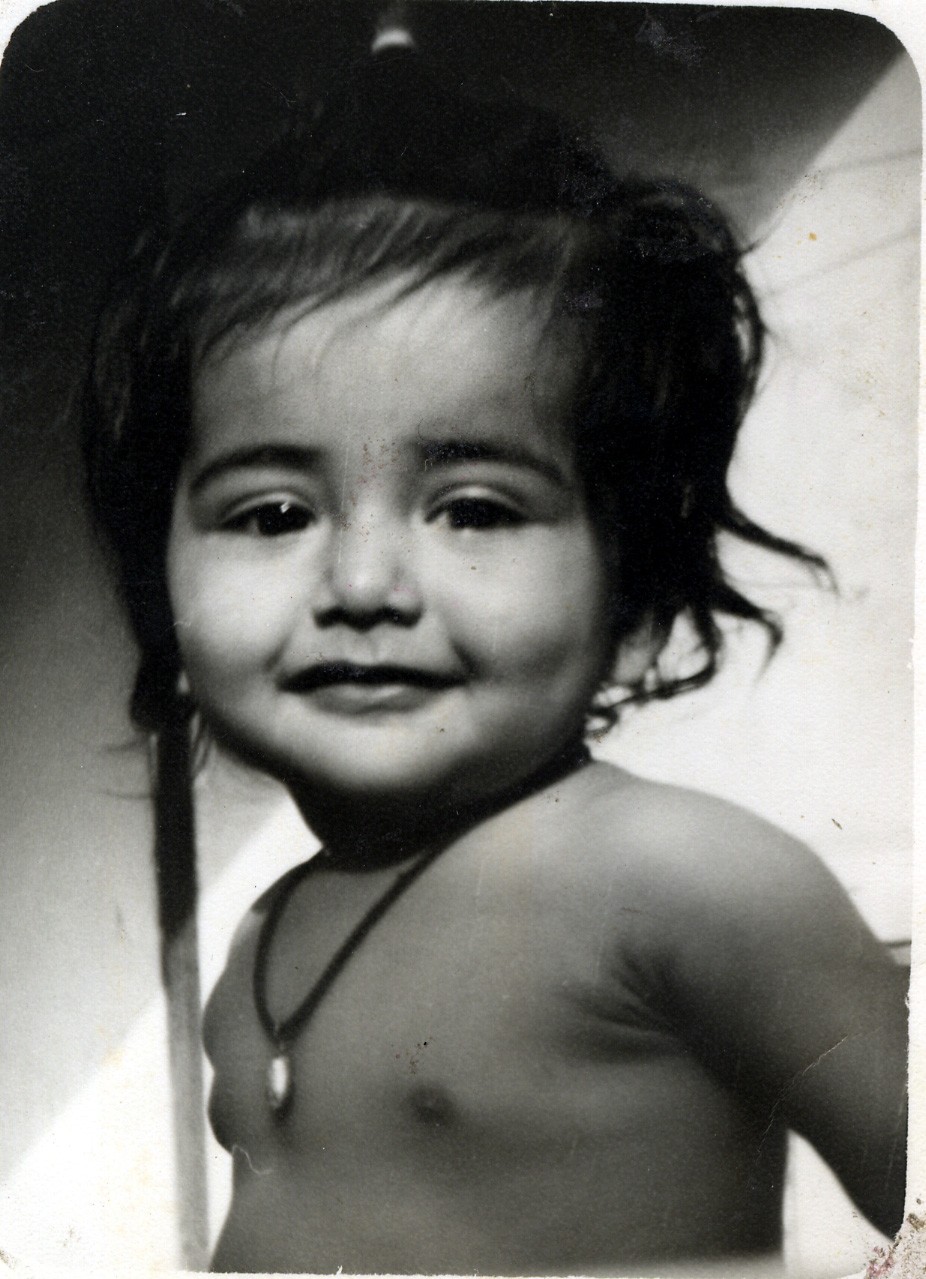

A Loving Nazar

In the autumn of this year, I decided to

grow a garden. A garden in concrete.

Like many Dilliwalas, I live in a DDA flat.

In fact, the DDA flat must be some kind of bleak mis en scene of my stationary

Dilli existence; it has stalked and enwrapped me all my life. I spent most of

my adult life growing up in a DDA flat. I got married and moved into a DDA

flat. I had a baby and moved into a new place closer to my parents who could be

my babysitters, and it was again, a DDA flat. I can move around in any DDA flat

with my eyes closed and brain on auto-pilot. I can maneouvre the light switches

like touch finger typing; in the backlit-keypad-less dark even. In the

afterlife, if I ever get into a hellish maze that remotely resembles a totally

sealed DDA flat, I will swiftly pull of a Houdini and be out in a jiffy.

The thing about a DDA flat is that it is a

collection of concrete walls and perpendicular angles, stacked one on top of

the other. A DDA flat is designed to exhibit the middle class lives of Delhi.

Just like the city, a DDA flat allows you no privacy; the walls and floors are designed to transmit

even the tiniest pin-drop silences. The balconies are stacked so that you can

see every inch of every dincharya

splayed in panoramic detail. Just like the city, you learn to make space in the

crush of bodies, breaths and gazes. A DDA colony is a collection of short

stories of Chekovian detail. Whether you look out of the window or not, there

is no escaping the information-overload of the Dilliwala’s dailyness.

Amidst all this, cross-hatching of gazes,

there is only one thing that relieves: some kind of green. If you are lucky, the community maali would have planted a thoughtful

tree or two around your concrete lego block, hopefully 10 years back. Maybe a

Saptaparini, or a Jamun even, would have grown high enough around your balcony,

trying as hard to shield you from the reckless probing as an aunty at a

Haridwar ghat, holding a makeshift dupatta-curtain

for her daughter to change behind.

I have always found this the most striking

thing about cities, the way the lives are worn, heard, felt, seen so openly on

faces, balconies, bodies. Despite the hallowed ‘urban apathy’. When I was

young, I found this intriguing, exciting even – the ease of being able to

access other people’s inner lives. But the more I traverse the city, and my own

life now, the more I feel that this tremendous display of detail bogs me down.

It inundates relentlessly like a persistent tsunami and does not recede from

sight.

In literature, academia, party

conversations, I’ve noticed how cities like Delhi are made out to be these

starved places; concrete landscapes, profusion of bodies; island-like

consciences; migratory memories and no belonging. Culture vs nature, in

hackneyed intellectual parlance. An imagined place that grows only where nature

has been cleared, like the very first mythical city of Delhi - Indraprastha -

that was built over the burnt-down Khandav Van. We don’t grow anything here;

things only ‘mushroom’, like concrete. We don’t really bend down and make

things; we sit and watch, we consume.

But there is a garden of the heart in a

city. How else, can any place survive hundreds of years of history? How can it

still make sense? How can it function, whirl itself into shape while still

looking like utter chaos? Sometimes this garden is only a memory of a place

where you ‘actually’ are from. Sometimes it is a hope – of a good life.

Sometimes it is just a survival trick – to secret away a part of you in a city

full of hungry, wily eyes. Sometimes, maybe, it is a desperate attempt to

romanticize in an atmosphere of apocalyptic, skeptic gloom.

How does this garden grow? I keep

wondering. Our water is toxic. Our air is among the most poisonous in the

world. The Dilli sun is relentless; its cold winds sadist. And yet, green grows

in this city. Peepul sprouts out of cracks in broken pipes, unasked and

uninvited. A Sadaabahaar with perfectly symmetrical pink pinwheel flowers has

been living in a crevice of my balcony for a year, unwatered, uncared for.

Hundreds of Amaltas trees burst in golden yellow plenitude and shower tarmac

with zabardasti ka joy, every June,

slaving under a sun that has been heatstroking everything it can find. Semal

and Gulmohars and Pilkhans colour skylines red without being asked to. Jaruls

and Jacarandas do the same with purple. And the Neems take care to keep their

foliage painterly dense, whether on the branch, or in heaps of dry leaves

lining the roads. Keekar spreads rampant.

I decided to grow a garden in my abode of

concrete. I am, after all, I thought, a

daughter of agricultural scientists. Two people who met because of the Green

Revolution in full swing in the 1970s, and who spent four decades believing and

telling farmers that you can grow a lot of green, whatever that might take.

Green led to me and I am being led by some invisible force to growing green. It

is destiny, I thought; not a revolution maybe, but an apt analogy. And as you

can see, I dig analogy. (And limp puns too).

It was not easy, what did I think? The

paucity of space (Can I possibly grow enough for a meal on a 1-foot wide

ledge?). The problems of making strong personalities ‘adjist’ and not rub the

wrong way (What grows with what? Will the basil get cross-polinated with my

paalak? Can I forbid the bees, really?) The fatigue and shortcut-psychology

that attacked after the initial euphoria had evaporated (So can any of these

interesting edible greens grow without the labour-intensive need to grow

saplings first?) The issues of survival (What will not be eaten up by dog and

baby?) The actual shallowness of my intentions (What will look pretty?) And of

course the terrible, niggling urgency. (Great sun! No smog! Chill in the air!

Leave everything; the baby, the house, the To Do. Sow the chard, sow the

chard!) I gave up trying to curate this garden after a point. I will just sit

on my bench, sip my tea or beer, and watch

this motley collection survive, I decided. I’ll let them know that I’ll just be

around, you know, for water or food or a good ‘wassup!’ stare. Let them bloom

up, or clamber down, or spread sideways. Let them rub against each other and

manage their emotions while jostling, like we Dilliwalas do. I will watch them

like I love to do in the disco; watching people dance.

And the darn garden grew. Tiny green

newborn leaves appeared, fluorescent almost, against the chocolate soil. There

were tiny hairy buds that bell-fanned into translucent-skinned yellow flowers.

Leaves shot upwards, without wasting time to shake of the seed that germinated

into them. Stalks appeared in unregulated sequence within the same pot, waking

up only when they felt the need to. There was a little choreography happening

in this whack garden.

Clearly, I had been forgiven for my

treachery, while the garden worked up a party, a rhythm. I’d been the most

illiterate maali ever. I left the

paalak seeds so exposed, pigeons began pecking in my trough, thinking I’m

offering birdfood. When I had to be out and about the whole day, I just

overwatered to compensate for my impending absence. Was too lazy to open the

manure bag when the flowers appeared (the scissors were in the kitchen, such a

long walk away). What then, really makes these grow? Was it the all-pervading

sun, the freak water showers (that I thought were not about climate change, but

green gods punishing the world for my negligent garden-watering habits), or the

belated khaad that I did finally

sprinkle over some of the well-performing pots? Or maybe all that green needs

to grow, is a passing glance, a moment taken aside for empathy, a loving nazar even. When one of the millions in

the city is able to set aside himself, and take a stroke of a second to really

look at another. At a living being trying to grow roots and leaves, giving a

spot of land a sense of place. It must be the loving nazar, I decide. Mine, or the neighbour’s.

Today I made the first harvest from my

patchy garden, this motley collection of creatures brought together with the

loving nazar. I plucked the basil

leaves by the handful, washed them well. I made a pesto, which I thought was

apt for this edible analogy. Pesto comes from the word pestare; ‘to pound’. Apt for this city and its life. A pesto is

both gourmet and rustic. It is versatile, and not at all a purist. A motley

collection: make it with whatever you have at hand. Don’t have pine nuts? Use

the almonds. No parmesan? Cheddar will do. Not enough basil? Even a tomato

pesto is possible. It’s the pounding that brings them all together, crushes the

ras out, blends them all together and

makes them worth something. Like your daily slice of bread. And that moment you

take out from your maddening day, to throw a loving nazar on what you just devoured.